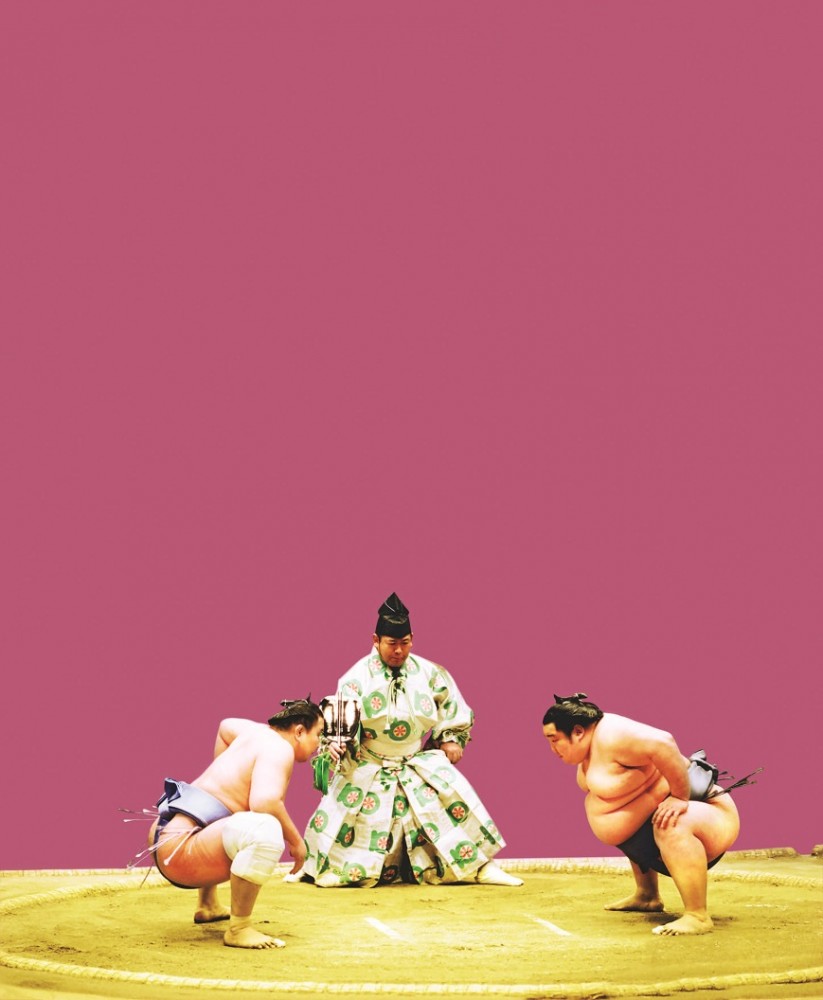

Sumo matches don’t last long, but the pomp and ceremony that precede them do, gradually building in intensity like a kettle on a slow boil. There are parades of fighters around the dohyo before each round of bouts, starting with the lowest-ranked rikishi early in the day and ending in early evening with the finest in the sport: household names in Japan like Hakuho and Kakuryu. There are processions of banner carriers, too, who look as if they could be standing out in front of a samurai army, though the embroidered banners they hold aloft to the crowd are actually advertising for brands as diverse as department stores and construction companies. And before each fight, there’s the posturing of the two fighters, intimidatory shows of strength in which they stamp their feet on the ground, slap their own ample bellies, and toss salt across the dohyo to purify the space.

All that ritual makes sense when you think of sumo’s roots in Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, where the fighting was initially a component of religious rites: a way to entertain the gods in the hope of gaining their favor for a good harvest. From there, sumo grew to be the entertainment of the Edo-era (1603–1868) working class, performed for a paying public as a way to raise funds for shrine and temple construction projects and then establishing itself as a recognized sport. Nowadays, not only Japanese, but wrestlers from Mongolia, eastern Europe and Hawaii occupy sumo’s professional ranks, who take part in six 15-day grand sumo tournaments annually. Even the standard seats for these sell out quickly, but the ringside boxes, where spectators sit on floor mats close enough to the dohyo to feel every slap and strain, are especially hard to come by—soon snapped up for corporate hospitality and VIPs.

Three of these tournaments—in January, May and September—play out at the Kokugikan in the Ryogoku neighborhood on what was Edo’s (as Tokyo was formerly known) merchant- and working-class east side. This is sumo central, the part of town in and around which many of the leading sumo beya (training stables) are located, where dozens of wrestlers live and train communally. Take a stroll here and you might see younger sumos running chores, out and about on Japan’s ubiquitous mamachari (“mom chariot”) shopping bicycles, perhaps picking up the ingredients for the hotpots the sumos cook and eat together in their living quarters.

Deep into Old Tokyo

The

Aman Tokyo is one of a small number of ultra-high-end hotels that can arrange exclusive sumo stable visits for its guests. It also offers guest-only journeys deep into other traditional aspects of Japanese culture that the typical traveler won’t get to experience. This includes one of the most iconic of all things Japanese, and perhaps the most misunderstood: geisha.

The journey takes privileged guests to the Akasaka neighborhood—one of six remaining hanamachi (“flower town”) areas in Tokyo where geisha still operate—and into Tsurunaka, perhaps the most exclusive of the capital’s remaining ryotei, highly private and highly priced traditional restaurants only accessible by referral, for an evening of fine dining, conversation and traditional entertainment.

Much like a day at the sumo, an evening at Tsurunaka is a succession of timeless elements: the bowed greeting of the kimono-clad owner after you have gone beyond the paper lantern that discreetly marks the ryotei’s entrance; the tatami-mat flooring and low tables of the private dining rooms, which over generations have seen politicians and VIPs meeting away from the glare of media and public scrutiny; and, of course, the geisha.